The master of political thrillers has passed away at age 86. A former pilot, war correspondent, and MI6 informant, the British author of The Day of the Jackal blended fiction and reality in chilling yet precise stories, redefining the spy novel. His books have sold over 75 million copies in more than 30 languages.

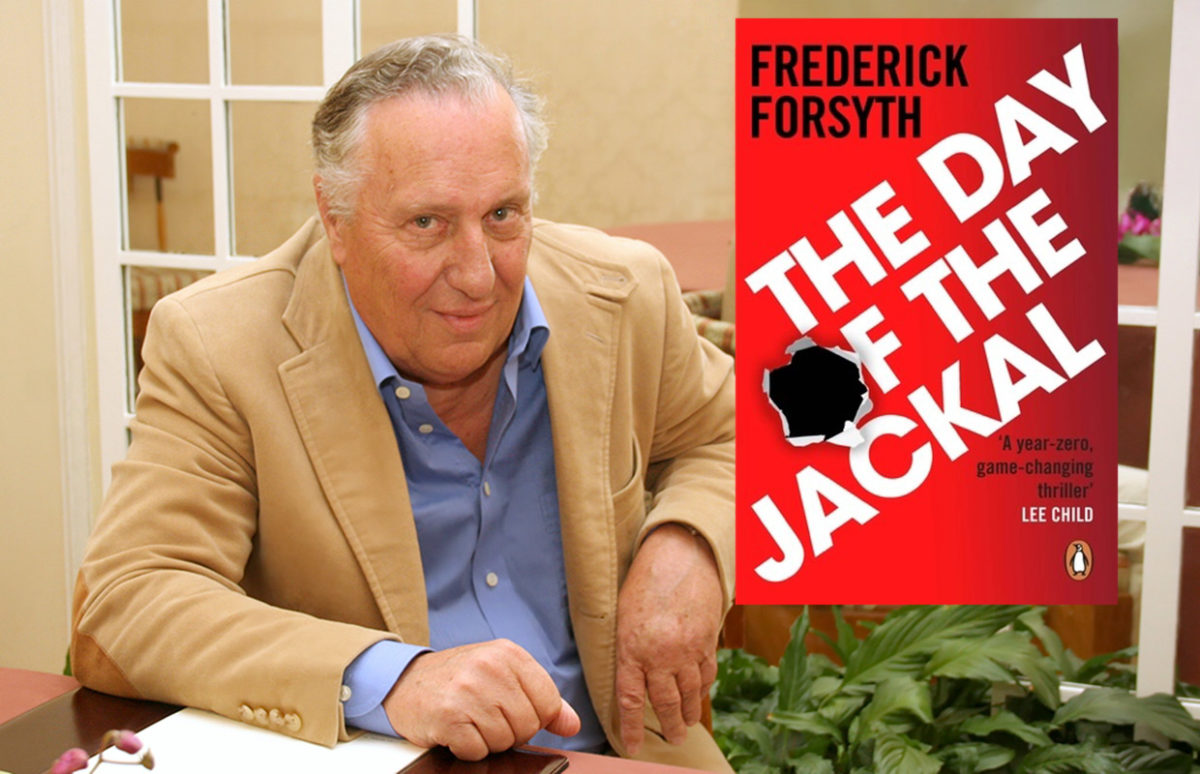

He wrote like a secret agent filing a report: terse, precise, without frills. Frederick Forsyth, a towering figure in political thrillers, died on June 9, 2025, at his home in Buckinghamshire, surrounded by family. He was 86. Behind this name—now synonymous with geopolitical tension and meticulous storytelling—was a man who lived many lives: a fighter pilot at 19, war correspondent in the most unstable zones on the planet, covert MI6 informant for more than twenty years... and above all, a novelist for whom fiction was just another way to convey reality.

Under the Sky, Danger

Forsyth’s first calling was military. At 19, he joined the Royal Air Force and became one of the youngest fighter pilots of his generation. There, he learned about aircraft, weapons, combat missions—technical knowledge he later recycled in The Shepherd and The Dogs of War. This military experience deeply shaped his imagination: for Forsyth, the action is always plausible, weapons are named with accuracy, and procedures described down to the comma.

He left the army to pursue journalism, another way to observe reality. He first worked for the Reuters new agency, then the BBC, which he eventually left after a standoff during the Biafran War in the late 1960s. When the broadcaster refused to send him further towards the front lines, he disobeyed and stayed on his own. He slept on the ground, shared fighters’ rations, witnessed famine and mass graves. This conflict, forgotten by the West, became a revelation: journalism, constrained by political and economic interests, was no longer enough. To convey the horror, he needed fiction.

The Spy Who Wrote

In 1971, he published The Day of the Jackal, a chilling novel about a hired assassin contracted to kill Charles de Gaulle. The book—resulting from meticulous investigations into the French secret services, power vulnerabilities, and the workings of the Organisation armée secrète (OAS)—revolutionized the genre. The style, inspired by war dispatches, broke with classic spy-novel codes: no flamboyant heroes, no glamorous seduction, but procedures, reconnaissance, and forgeries. A clandestine world told with ruthless realism.

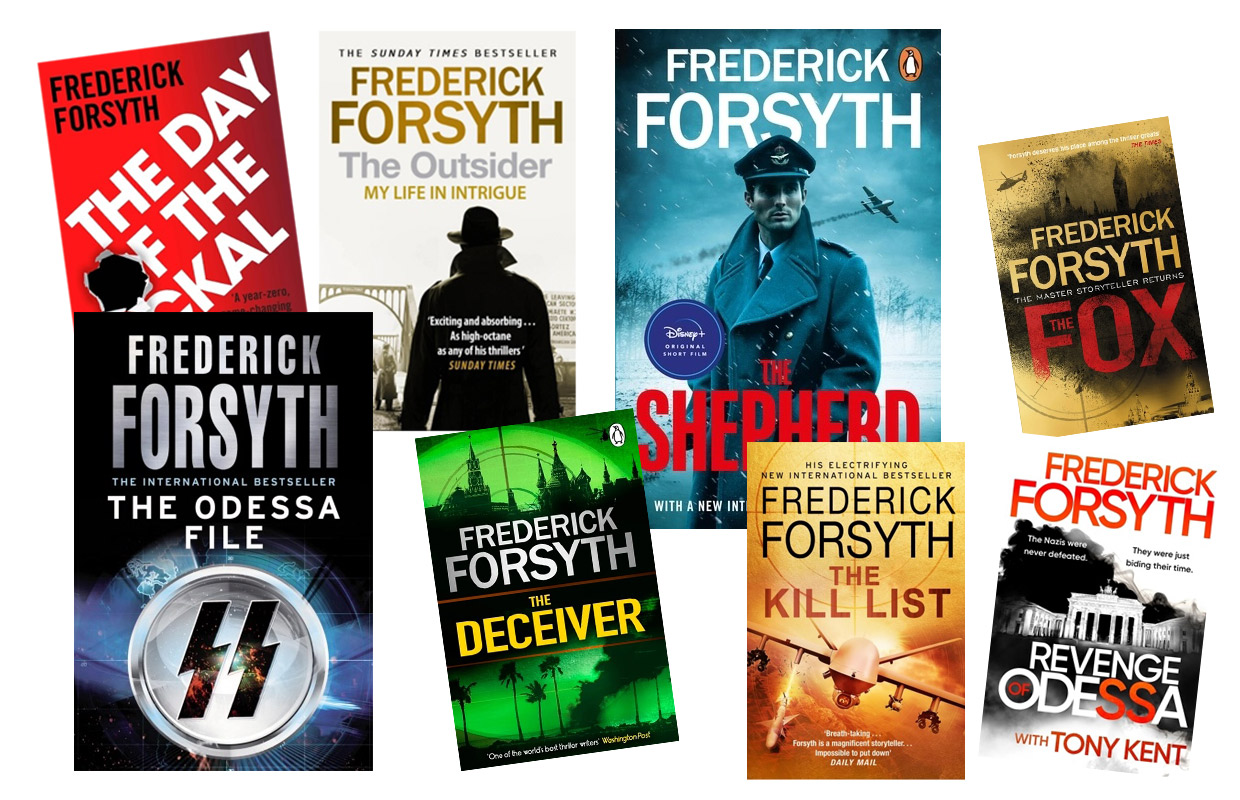

Success was immediate. The novel became a bestseller and was adapted into a 1973 film by Fred Zinnemann. In 2024 the book was extensively reimagined for a TV series with Eddie Redmayne as the Jackal (available on Prime in France). Forsyth followed with The Odessa File, The Dogs of War, The Fourth Protocol, The Devil’s Alternative, The Cobra... stories featuring arms dealers, mercenaries, Soviet spies, and nuclear conspiracies. His talent lay in making each novel an undercover journalistic investigation, based on facts, names, maps, and often on information no one had dared reveal before.

In 2015, he revealed a secret side of his life: he had served as an MI6 informant for over twenty years. Under the cover of his journalistic work, he reported to London sensitive information gathered in Africa and Eastern Europe. This double life—both pen and ear in the shadows—gave his work rare power. Forsyth didn’t imagine espionage—he lived it from within.

The Style of Truth

His books—a total of about fifteen novels, all translated into more than 30 languages—have sold over 75 million copies. They continue to circulate in airports, libraries, and film archives, often adapted for the screen with his involvement in the screenplay. He imposed a thriller grammar: short sentences, factual narration, mounting tension, and above all, obsessive fidelity to detail. For him, documentation was king. Every weapon, every code, every infiltration plan was verified, cross-checked, and validated.

Not fond of literary socializing, Forsyth preferred embassy corridors, foreign hotel bars, dusty airstrips. He wrote to understand what governments kept silent, to expose the manoeuvres behind crises, to give shape to the grey truths that the press—too constrained—could not communicate.

With his passing, a certain idea of the spy novel dies. A literature without effects or pathos, but taut as a wire. That of a man who looked at the world without illusions and chose to tell us about it with almost surgical precision. Frederick Forsyth was not a novelist from the shadows—he wrote from within the shadows.