Canada pioneered an experiment on a universal basic income for all citizens in the 1970s. Now, one province, Ontario, has promised another trial. And other countries or regions are also toying with a basic income for all.

In 1974, when Pierre Trudeau was Prime Minister, the federal government and Manitoba Province launched a four-year minimum income experiment called Mincome. In 2017, with Trudeau's son Justin in power, Universal Basic Income (UBI) is again sparking interest, in Canada and around the world. But the term UBI covers many different models.

Mincome

The Mincome experiment took place in the provincial capital Winnipeg and a small rural town called Dauphin. In Winnipeg different models were tried, in Dauphin just one was offered. Thirty per cent of the population in Dauphin qualified for help through the scheme, which offered a guaranteed, reliable income, although only 40% of those accepted help. Where family members worked, the Mincome payment was reduced, but only by 50 cents for each dollar earned, so as not to discourage work.

There is therefore a wealth of data available for Dauphin, but it wasn't analysed after the scheme was abruptly stopped after four years and a change of government.

In the mid-1980s, sociologists have unearthed the data and started working on it. Preliminary results suggest that Mincome didn't discourage working, though it did encourage families to allow their sons to finish high school rather than dropping out to start paid work to help the household. Researcher Evelyn Forget also believes that it led to a significant improvement in health, and consequently savings in health care: an 8.5% drop in hospitalisations for example.

This is one of the main arguments of pro-UBI campaigners -- that UBI wouldn't be a one-way street, with money from the state to the population, but that it would allow savings in other areas. First and foremost in the cost of assessing and policing those who currently receive different types of welfare payments.

Most models of UBI assume that it will to some extent be a re-allocation of current government spending on welfare payments and tax credits. But the crucial element with Mincome was that there were no restrictions on what the money could be spent on.

Participants Forget and other researchers have interviewed talk about many different uses. Eric Richardson's family received Mincome when he was a child, and it gave him the opportunity to visit a dentist for the first time at age ten. The dentist discovered 10 cavities.

One woman describes how Mincome allowed her to begun a career she loved. She was a single mother to two children and previous welfare payments required her to stay at home as a child carer. She used the Mincome payments to train as a librarian, and got a part-time job at the library. She went onto to have a long career as a librarian.

Beth Wallace and her husband had a small farming business. They used the Mincome cheques to buy a used truck to transport livestock. It is still running today.

Left or Right?

UBI is a policy which has been embraced by policy makers on both sides of the political divide. Republican President Richard Nixon tried unsuccessfully to get an UBI bill through Congress in the late 1960s. In Canada, it was Trudeau’s centrist Liberal Party that championed it. Today, it is Ontario’s Liberal provincial government which is planning a new pilot of UBI.

The Ontario scheme is still under discussion, and will probably test different models of basic income, which could include:

Universal Basic Income: given to all citizens regardless of income, but some is “clawed back” through income tax.

Income Top-Up: tops up income to a basic level, so only concerns citizens on lower incomes.

Negative Income Tax: when citizens declare their income for tax, those who don’t reach the taxable threshold actually receive money from the government rather than paying tax.

The pilot should get underway in 2017. Other pilots are being launched in Finland, the Netherlands, California and Scotland.

From Massachusetts to Kenya

The projects discussed up till now concern wealthy, industrialised countries. But advocates say Basic Income could also solve extreme poverty in the developing world, and could potentially be more efficient than existing aid schemes. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Give Directly project points out that, “700 million people around the world live in extreme poverty. It would take $80 billion in cash transfers to move everyone above this poverty line, while the world spends almost twice that in global aid every year.”

Give Directly is leading a major, 12-year Basic Income experiment in Kenya. It aims to be the biggest experiment of its kind so far, and carried out with the sort of rigorous methodology you would expect from MIT.

The project will test 4 models in a number of rural villages, totalling 26,000 people. Two models will provide a monthly income for every adult, in one case for 12 years, in the other for two. A further group of villages will receive single, lump-sum payments equivalent to the 2-year monthly payments. And a final group is the control, so they will receive nothing, but be surveyed for comparison.

The Give Directly project is crowdfunded. Almost $24 million of its $30 million budget has already been raised from supporters across the world.

Copyright(s) :

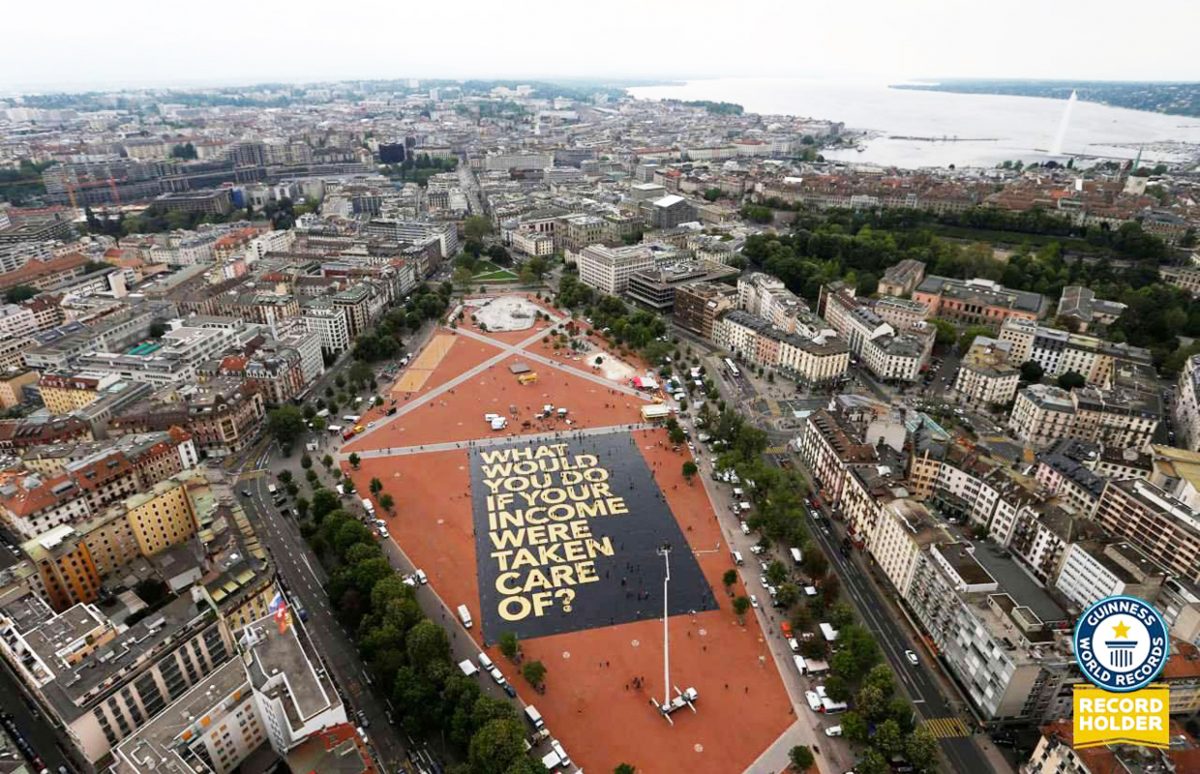

Gruneinkommen

Ontario Government

Give Directly