This year sees the 400th anniversary of the ancestor of today’s Thanksgiving holiday in the U.S.A. 400 years after the meal shared by Pilgrims and Wampanoag Indians in Massachusetts, efforts are gaining ground to see the event from the points of view of both communities.

When the Mayflower brought 102 Puritans to New England in 1620, archaeologists estimate that local Wampanoag nation had been living in the area for 12,000 years. The Puritans named the town they founded Plymouth. To the Wampanoag, it was Patuxet. These colonists were not the first visitors from Europe they had encountered. In fact, just four years before, European traders had exposed the Wampanoag to yellow fever, which had decimated the population. An estimated 45,000 Wampanoag, two-thirds of the population of 69 tribes, died.

The Thanksgiving story as it is told today was that the Puritans held a feast to celebrate a good harvest, and invited the local Indians to join them since they had helped them learn to cultivate indigenous crops.

There are only two short references to the feast in the records of Plymouth colony. One of the colonists, Edward Winslow, wrote in a letter:

Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after have a special manner rejoice together […] many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted.

There is no record that there was a repeat of the event. In New England, traditions of harvest festivals continued but the “first Thanksgiving” was largely forgotten about until Abraham Lincoln declared a national Thanksgiving holiday in 1863 the midst of the Civil War.

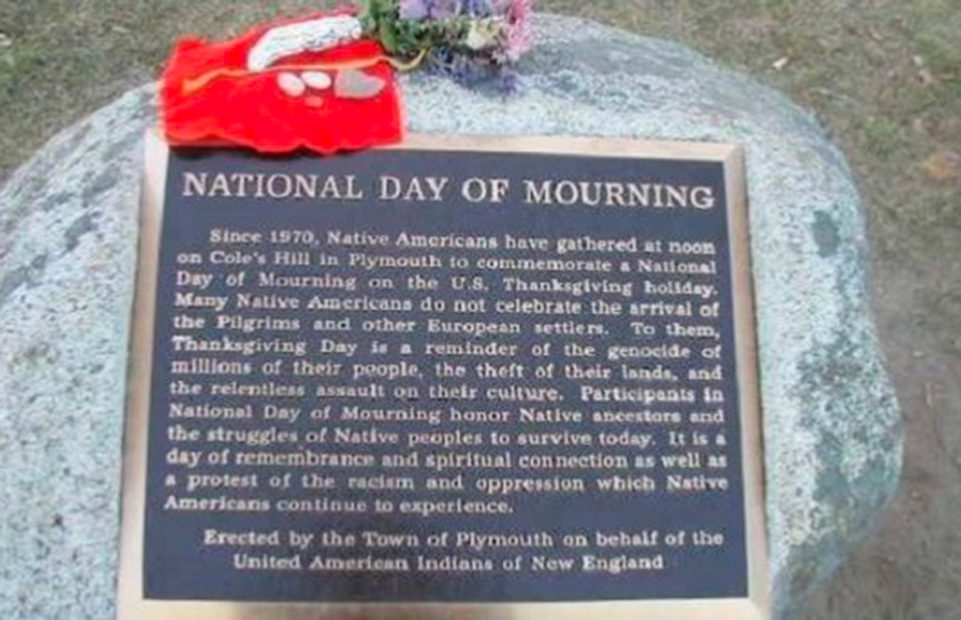

National Day of Mourning

The cosy image of Puritans and Indians sharing a meal ignores the history of European colonisation of the United States: confiscation of land, forced displacement and assimilation, decimation of the population. The Wampanoag leader the Massasoit referred to by Winslow (the Massasoit was a title, not a name), had signed a treaty with the colonists earlier in the year. Like so many others, it was later ignored by the Europeans.

In 1970, when native groups were beginning to demand civil rights through the formation of the American Indian Movement, indigenous people in Massachusetts started a ceremony in Plymouth each Thanksgiving, which they renamed the National Day of Mourning. It has taken place every year since.

Native groups have been instrumental in pushing for a more authentic telling of the Thanksgiving story and the Plymouth colony. The Plimoth Plantation living-history museum, for example, has recently been renamed Plimoth Patuxet Museums and has opened an exhibition called “We Gather Together: Thanksgiving, Gratitude, and the Making of an American Holiday”. Many native groups had pushed for native representation in the 400th anniversary celebrations of the arrival of the Mayflower last year, and that had been planned before the celebrations were cancelled because of COVID.

But much more remains to be done. Brian Weeden, Chairman of the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, one of two federally recognised Wampanoag tribes, points out, “The Native Americans who welcomed everybody lost all of their land. Today, we only own half of 1% of our ancestral territory. I think that just speaks volumes. Four hundred years later, I tell everyone we don’t have much to be thankful for.”

Copyright(s) :

Smithsonian

United American Indians of New England

Mashpee Wampanoag

> A Native American View of Thanksgiving

> The Voyage of the Mayflower

> Thanksgiving with Wampanoag and Pilgrims

> Thanksgiving Stories

> Thanksgiving on the Web

Tag(s) : "Native Americans" "Pilgrims" "Puritans" "thanksgiving" "The Mayflower" "the Pilgrim Fathers" "U.S. Constitution" "U.S. culture" "U.S. history" "Wampanoag"