In 1920, almost 150 years after the United States declared that “all men are created equal,” American women got the right to vote… 27 years after women in New Zealand did. American suffragists worked for almost 80 years to obtain that right. And there’s still work to do today.

As is often the case in the United States, the movement progressed state by state before arriving at the national level. In 1869, the state of Wyoming became the first in America where women could vote. A dozen other states, most of them in the West, followed over the years.

Seneca Falls Convention

Seneca Falls Convention

The first formal demand for women’s suffrage came in 1848, after the Seneca Falls Convention. The Convention was a public meeting to discuss women’s rights in general, not just voting rights. Participants at the Convention passed a resolution in support of women’s suffrage. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, one of the organisers, who would become a leader of the suffrage movement, drafted a statement based on the Declaration of Independence:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

—Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Declaration of Sentiments, 1848

Guerilla Voting

Before the Civil War, Susan B. Anthony was an anti-slavery activist. In 1869 (four years after the abolition of slavery), Stanton and Anthony co-founded the National Woman Suffrage Association.

In 1872, Anthony voted in New York state in the presidential election, arguing that under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified four years previously, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States… are citizens of the United States.” She was charged with voting illegally and the judge refused to let her speak in court. When she refused to pay a fine, he refrained from sending her to jail, which would have allowed her to take an appeal to the Supreme Court. Newspaper articles about her arrest were excellent publicity for her cause.

New Forms of Protest

In the early days of the suffrage movement, the suffragists had used classic American methods for obtaining political change: signing petitions and lobbying state and federal legislatures. But as the twentieth century dawned with no sign of progress, they turned to more visible forms of protest designed to draw media attention, some of them borrowed from the British Suffragettes.

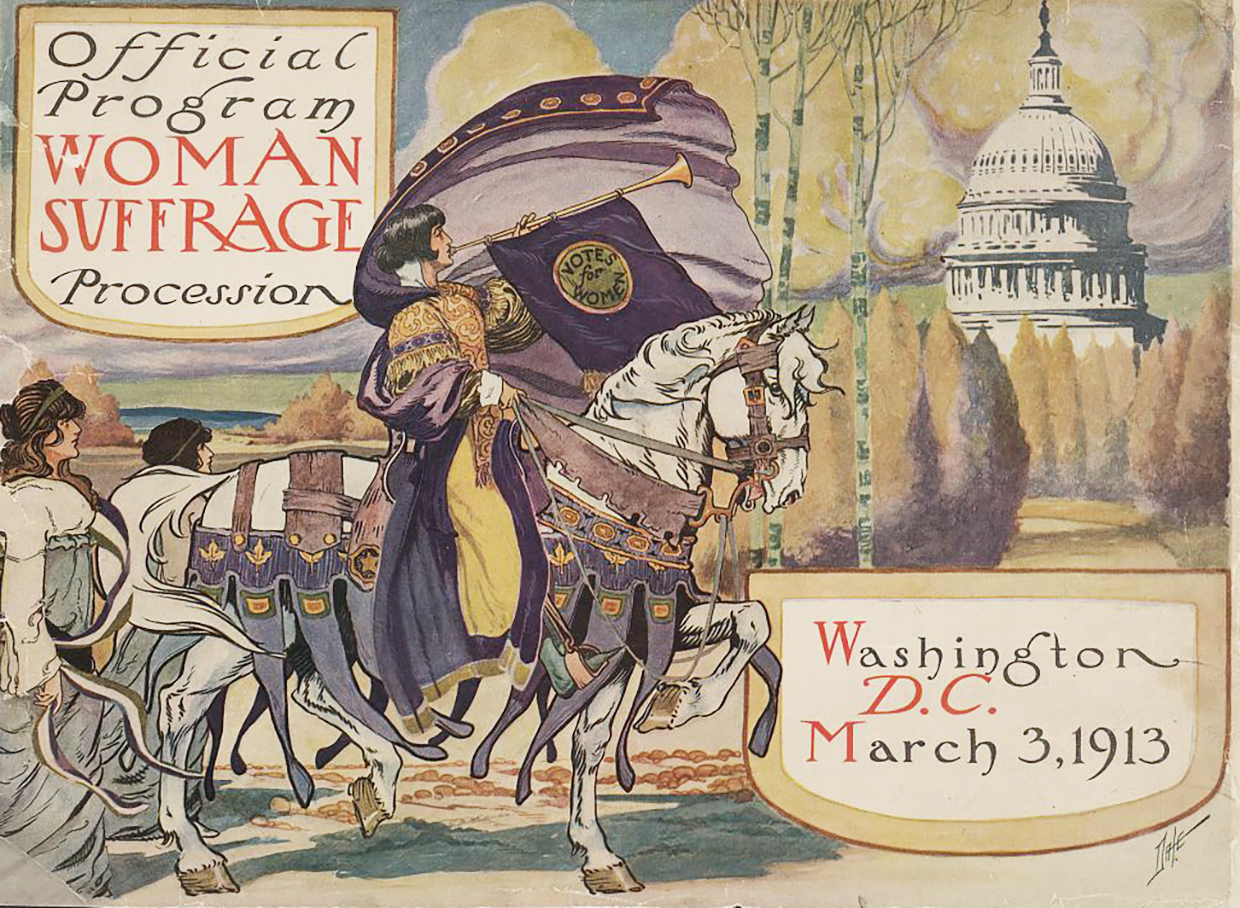

On March 3, 1913, the first National Suffrage Procession took place on the National Mall in Washington DC, timed to coincide with President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. It was the first such non-violent parade on the Mall, which has since seen such historic demonstrations as the 1963 civil rights March on Washington.

The following year, a women’s suffrage amendment was introduced to Congress, but it failed.

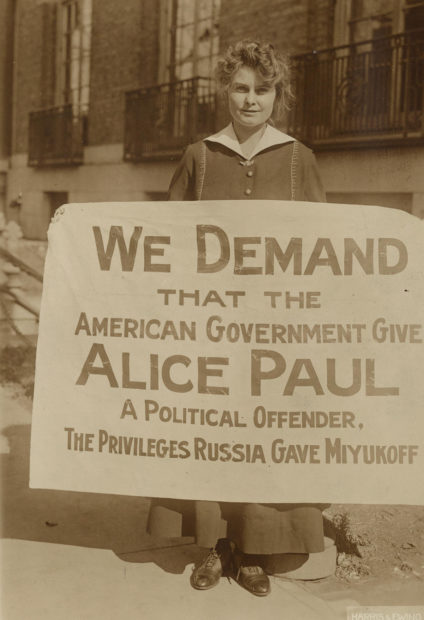

In January 1917, the National Woman’s Party started picketing the White House, again the first time this form of protest was used. The “Silent Sentinels” stood outside the gates with banners bearing slogans such as “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” The women returned every day. In April, the U.S.A. entered World War One, and from June, the picketers started being arrested for this “unpatriotic” protest. Pointing out that the President was denying them the very liberties the country was supposed to be fighting for in Europe didn’t stop the women being jailed for up to six months.

In January 1917, the National Woman’s Party started picketing the White House, again the first time this form of protest was used. The “Silent Sentinels” stood outside the gates with banners bearing slogans such as “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” The women returned every day. In April, the U.S.A. entered World War One, and from June, the picketers started being arrested for this “unpatriotic” protest. Pointing out that the President was denying them the very liberties the country was supposed to be fighting for in Europe didn’t stop the women being jailed for up to six months.

Jailed suffragists, like their sisters in Britain, went on hunger strike in prison, demanding to be considered political prisoners. And as in Britain, the prison authorities responded by brutally force feeding them.

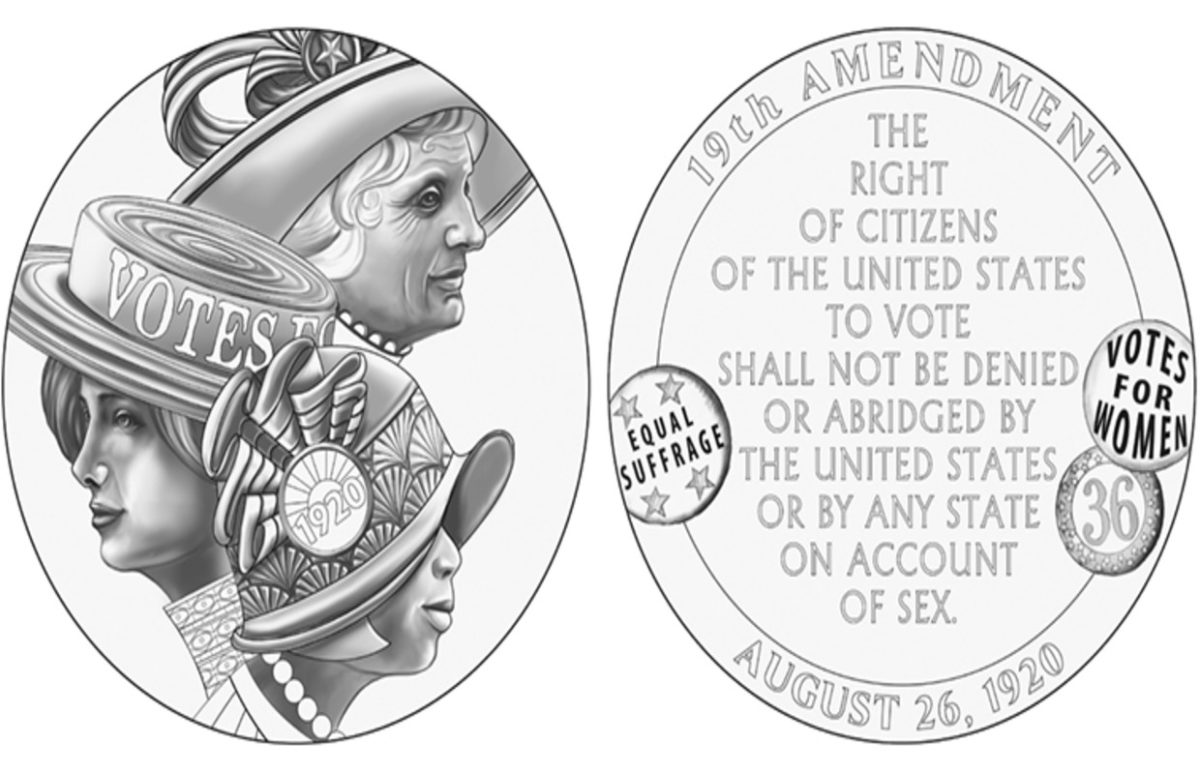

The President finally endorsed the suffragists’ demands for a 19th amendment to the Constitution guaranteeing women the right to vote, but it still took three attempts to get it passed by the Senate. It was passed on 4 June, 1919. However, 36 states, two-thirds of the total, had to ratify it before it became law.

Victory But The Fight Goes On

In August, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment and it was signed into law on 26 August. The ratification process continued in the other states: Mississippi only finally ratified it in 1984.

But that wasn’t the end. The same sort of tactics that stopped African American men from exercising their right to vote (poll taxes, literacy tests, intimidation, etc) were used against women. There was also a strong societal bias that many women had to overcome to make it to the polls.

And voting was only one area in which women’s situation was less advantageous than men’s. National Woman’s Party leader Alice Paul drafted a proposed Equal Rights Amendment which was introduced to Congress every year from 1923 till 1972, when it finally passed but was not ratified.

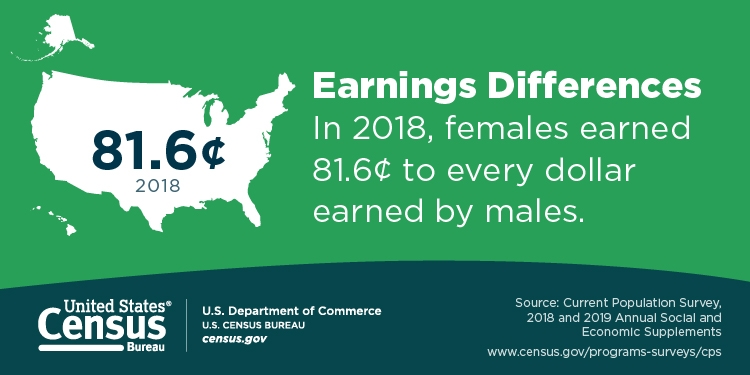

The 1963 Equal Pay Act tackled one of the issues the ERA sought to address. It was supposed to guarantee the same pay for men and women for equivalent jobs. Yet the gender pay gap in 2018 was still 19% :

100 Years and Still Waiting

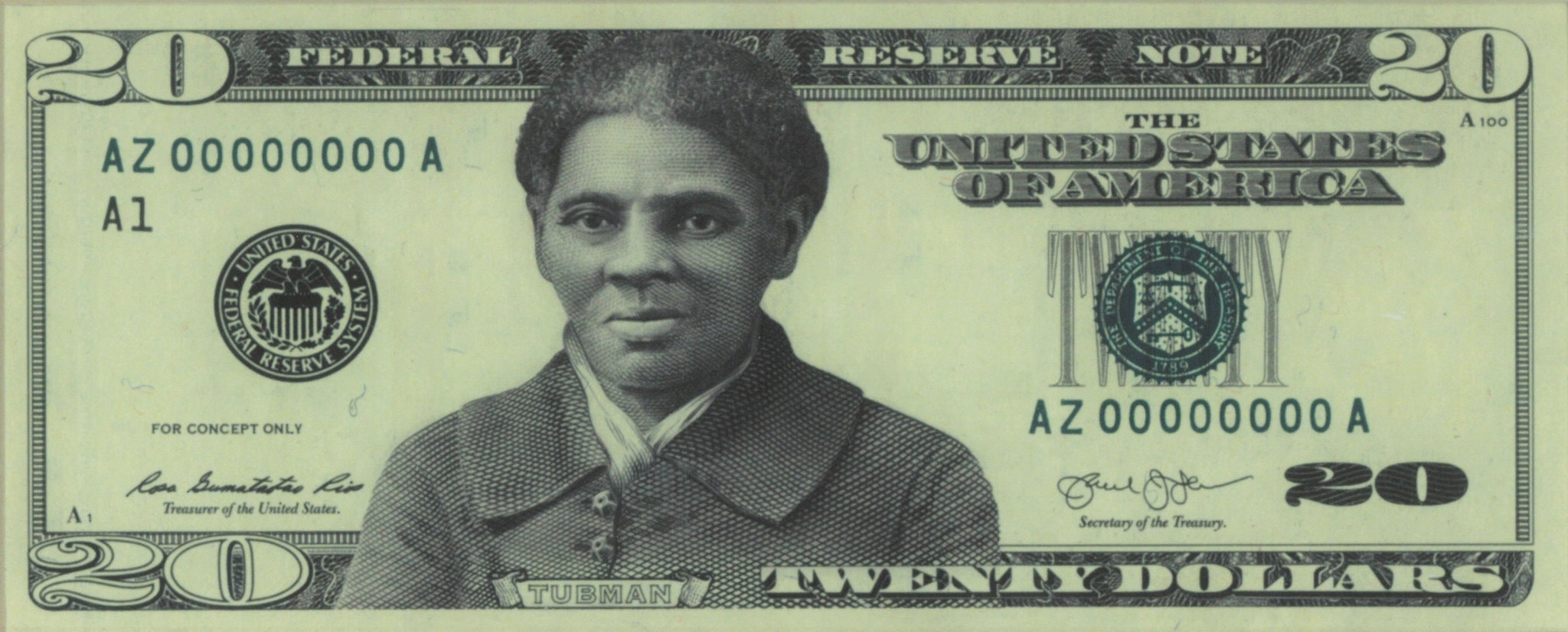

The Women on 20s organisation has long campaigned to have the first ever woman appear on a U.S. banknote in time to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment. After a national poll chose Harriet Tubman, former slave, abolitionist and prominent suffragist, the U.S. Treasury agreed to at least reveal a design for a new $20 dollar bill with her image in 2020. But the apparent opposition of President Trump to the bill has meant the new bill has been delayed indefinitely.

Copyright(s) :

U.S. Mint

Library of Congress

U.S. Census Bureau

D.R.

> Teaching about U.S. Women’s Fight for the Vote

> Celebrating Votes for Women

> Suffragettes Interview

Tag(s) : "Alice Paul" "civil rights" "Elizabeth Cady Stanton" "feminism" "gender equality" "Harriet Tubman" "Suffragists" "Susan B. Anthony" "U.S. politics" "universal suffrage" "votes for women" "voting" "Woodrow Wilson" "WWI"