Until the recent past, the electoral college was barely mentioned in descriptions of the U.S. Presidential electoral system. But then came the 2000 election, when George W. Bush lost the popular vote, but won the majority of electoral college votes. And 2016, when Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by a 3 million margin, but Donald Trump won the electoral college vote 304 votes to 227.

Previous to the 2000 election, there had only been two occasions when the electoral college had done anything other than "rubber stamp" the candidate elected by the popular vote, and the more recent of those was in 1888.

How Does the Electoral College Work?

There are 538 electors. Each state has an equivalent number of electors to their senators and representatives in Congress. A list of electors is proposed by each party and is presented on the ballot on the day of the election. In all but two states*, the candidate who wins the popular vote in that state receives the state's electoral college votes, so, in effect, the list proposed by the winning candidate's party. The electors are usually party supporters, workers or volunteers.

In December (14th this year), the electors for each state meet in their state capital and vote. Congress then meets in January (6th this year) to count the electoral college votes, just in time for the Inauguration.

This TedEd video says it in images:

Towards an End of the Electoral College?

There have been attempts in recent years to end the electoral college system, which is perceived as being anti-democratic.

From the outset, the Electoral College, as well as Congress, was designed to favour the smaller states, which are disproportionately represented. Every state, no matter its size, has two senators. Members of the House of Representatives are distributed according to the population of the states, but overall representation is mathematically weighted towards the smaller states.

The system intrinsically tends to produce a bigger majority for one candidate than they have in the popular vote (just as in Britain's "first-past-the-post" system, a party can win a slim majority nationally but receive a disproportionately large number of seats in Parliament.) In 1960, for example, John F. Kennedy received 34,277,096 votes: 49.7%. His Republican rival, Richard Nixon, won barely 150,000 less: 34,107,646 or 49.5%. Yet Kennedy received 303 electoral college votes whereas Nixon had only 219.

As long as the candidate who won the popular vote also got a majority of electoral college votes, it didn't seem to bother Americans if the numbers appeared out of kilter. The problem came when candidates who came second nationally came out ahead in the electoral college, as in 2000 and 2016.

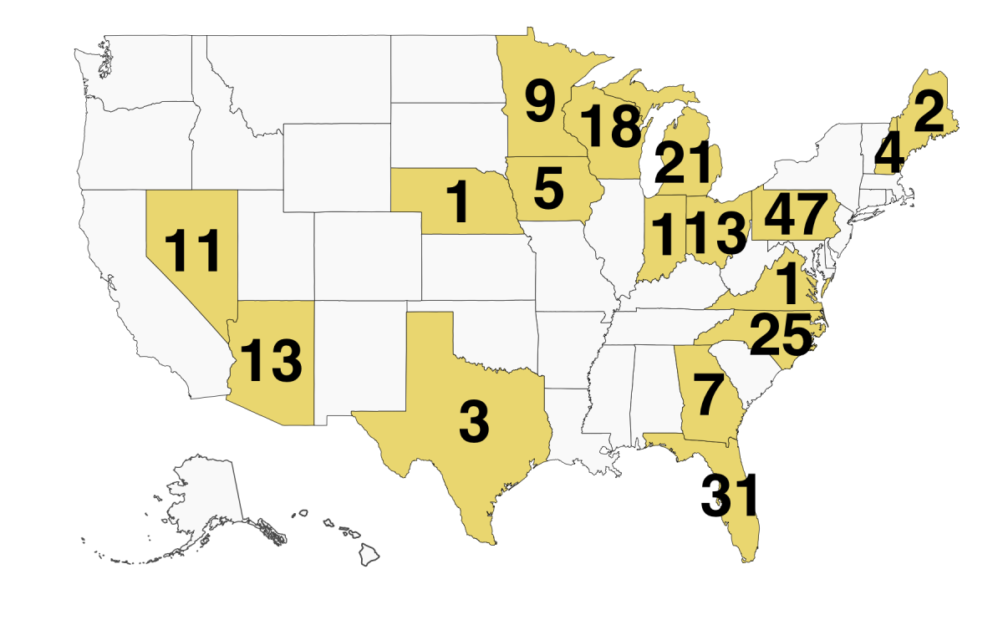

The current system encourages candidates to focus their attention on the big states, and particularly the swing states they hope to win from the other party. For example, FairVote, a non-profit organisation advocating for electoral reform, produced this map showing that 204 out of 212 election events in the 2020 election, from 28 August to election day, took place in just 12 battleground states.

Proponents of the abolition of the electoral college say that a direct popular vote would make every vote count. However, abolition would involve an amendment to the Constitution, a long and arduous process., so alternative paths have been explored.

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact aims to require states to give their electoral college votes to the candidate who wins the national popular vote, not necessarily the one who won in their state. Since the Constitution doesn't dictate how states should select their electors, the compact could change the system without a Constitutional amendment. Since 2007, 15 states and the District of Columbia have voted to join it, with a combined 196 electoral votes. They need to reach 270 electoral college votes for the compact to become active, so for now they continue with the existing system.

The organisation backing the compact, and a more far-reaching National Popular Vote Bill, National Popular Vote, produced this video explaining the concept. It features Democratic Congressman for Maryland and law professor Jamies Raskin.

If this system had been in place in 2020, Joe Biden would have been declared the winner on election night, rather than have the process drag on for days.

* The two states which don't use the "winner takes all" system for their electoral votes are Maine and Nebraska. These states allocate two electoral votes to the state popular vote winner, and then one electoral vote to the popular vote winner in each Congressional district (2 in Maine, 3 in Nebraska). Neither has joined the NPV Compact.

> U.S. Presidential Election Webpicks

> U.S. Youth Vote Videos

Tag(s) : "Biden" "Congress" "electoral college" "EMC" "JFK" "Kennedy" "Nixon" "parcours citoyen" "president" "Trump" "U.S. elections" "U.S. president" "White House"