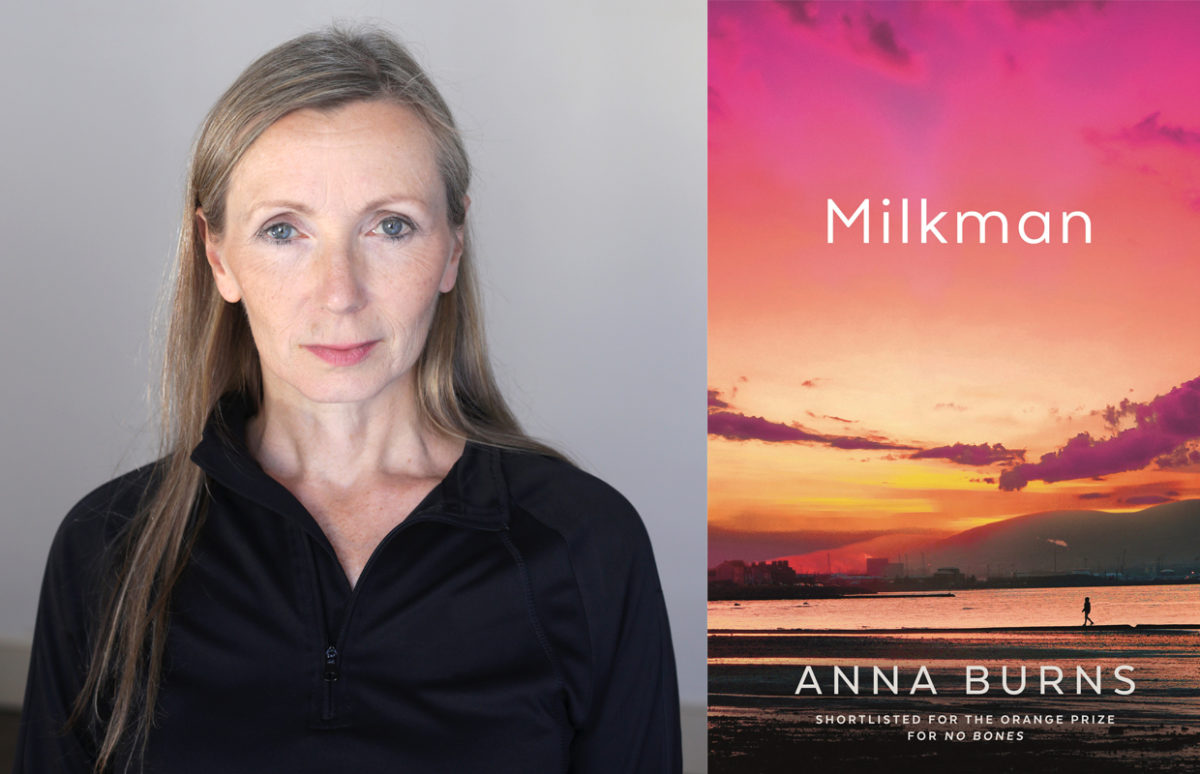

The winner of this year’s Man Booker Prize is a book about a divided society. Its author, Anna Burns, hails from Belfast, and the unnamed city in Milkman has echoes of the Northern Irish capital during the Troubles. But, as the chair of judges Kwame Anthony Appiah says, is about what happens in sectarian societies everywhere in the modern world.

The main protagonist in Milkman is simply called "middle sister". Like all the characters, she is named more for her function than identification — like "nearly-boyfriend" or "first brother-in-law". She is 18 and doesn't really fit into the mould of her family or her close-knit community identified by religion. She loves reading — in fact she reads walking down the street, a strange trait that makes her stand out from the crowd.

She further stands out when she attracts the interest of the milkman. He doesn't deliver milk, he is a local paramilitary. (The IRA used to deliver petrol bombs in milk crates during times of unrest.) The milkman, older and married, wants to have an affair with middle sister. Despite the fact that she resists his advances, the entire community is soon convinced that the affair is reality.

Like in any small community, gossip and rumour are powerful tools that regulate community members behaviour. Burns, who has previously published two novels and a novella, may be writing about 1970s Belfast, but readers, especially women, from small communities all over the world can recognise middle sister's dilemmas.

Despite the serious subject, the book has been praised for its humour. It was the unanimous choice of the Booker judges. The chair of judges, Appiah, was entranced by Burns' narrative voice. "It is an amazing voice," he said. Appiah, "Burns uses language in a way you haven’t heard before. You hear [middle sister's] voice in your head and you’ve never heard one like it before."

Asked why she used not proper names in the book, Burns replied, "The book didn’t work with names. It lost power and atmosphere and turned into a lesser - or perhaps just a different - book. In the early days I tried out names a few times, but the book wouldn’t stand for it. The narrative would become heavy and lifeless and refuse to move on until I took them out again. Sometimes the book threw them out itself."

Names are slippery things in Belfast. As middle sister says about her evening class in French, "I was downtown, which meant outside my own area, which meant outside my own religion, which meant I really was in a class counting people who really did have the names Nigel and Jason." Names are indicators of class and religion, limiting people to a role, a small space. Middle sister's habit of replacing proper names with functions lets her take back a little power in a world that contrives to keep her powerless.

You can read a sample chapter on the publisher's site.

Find a sequence on the Troubles in Speakeasy Files 3e: it looks at the period through the arts, with an extract of the film '71, poetry and murals.

Tag(s) : "Belfast" "literary prize" "literature" "Man Booker" "Northern Ireland" "sectarianism" "Speakeasy Files 3e" "the Troubles"