After elections to the Scottish Parliament, the Scottish National Party has emerged the leading party for the fourth consecutive election, achieving just one seat short of a majority in an electoral system specifically designed not to produce overall majorities. The party of First Minister Nicola Sturgeon had campaigned on the promise of a new independence referendum, dubbed IndyRef2, after the country rejected independence in the 2014 referendum.

It was one of a series of elections which took place in the UK on 6 May: for the Scottish and Welsh devolved parliaments as well as for various councils, “metro mayors” and police commissioners in England.

The devolved parliaments were created in 1999. The Scottish Parliament at Holyrood and the Welsh Senedd control many aspects of daily lives in their nations, such as education and the health service.

Unlike elections to the national parliament in Westminster, the devolved parliaments don’t use the traditional “first past the post” system, which generally means that a party can win a majority of seats without actually winning a majority of votes in the country. They use a form of proportional representation (PR) which results in a much closer link between the number of votes received and the number of seats. Voters have two votes: one for the constituency they live in and one for the region.

Whenever constitutional reform is called for in Westminster, one of the main arguments against moving towards PR is that it tends to make it difficult for a single party to gain a majority, and leads to coalitions. Yet the SNP has managed to form the last three governments, even gaining an overall majority in 2011, and will form the next this week.

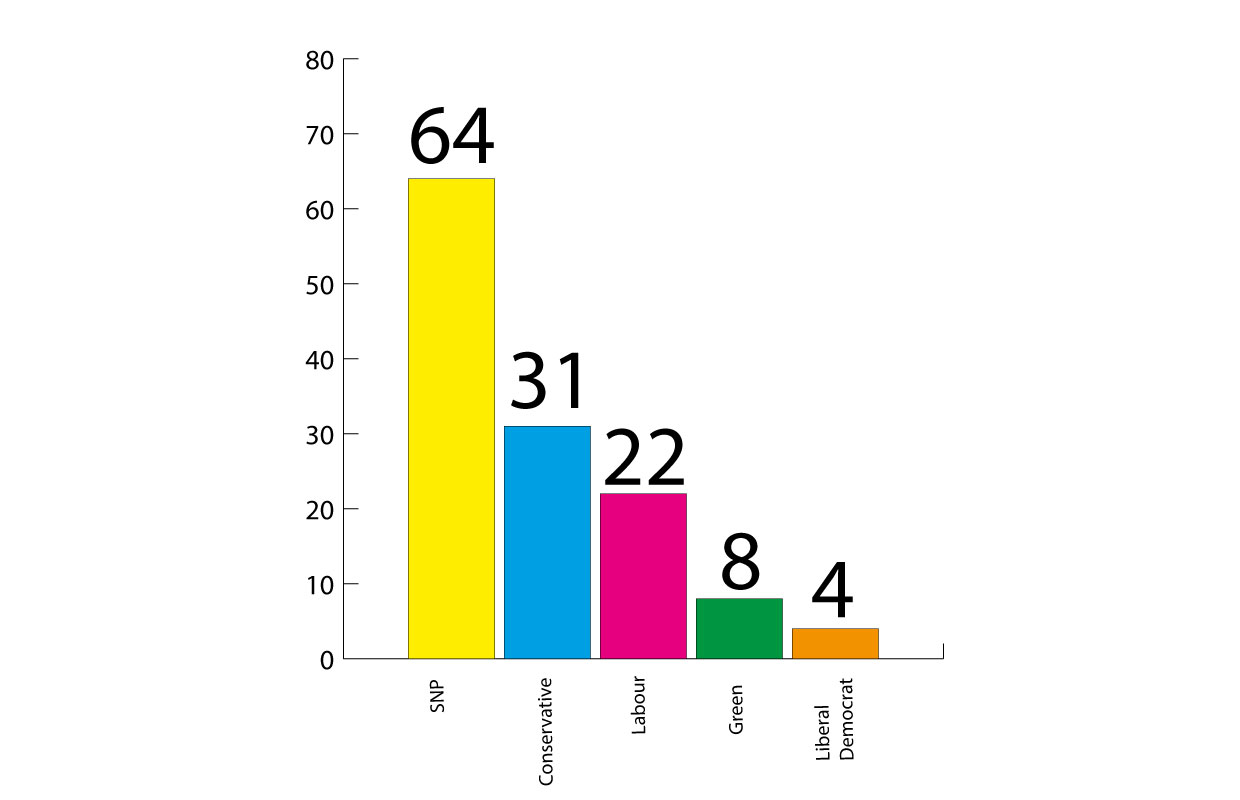

Results of the 6 May election to Holyrood:

From a party which was founded with the single aim of obtaining independence, it has become a party of government. The SNP’s handling of the Covid epidemic, with Nicola Sturgeon’s calm, daily press briefings providing a sense of stability in a difficult time, was perceived by many voters as a marked contrast with the ever-changing policies revealed in Westminster briefings.

Another Referendum?

The issue of independence dominated the Scottish election. Yet, when there was a referendum in 2014, voters chose by 55% to remain in the UK. At the time, the SNP, said it was a “once in a generation” plebiscite.

However, nationalists have been arguing since 2016 that the Brexit referendum moved the goalposts, since it took Scotland out of the European Union despite every single Scottish constituency, and 62% of voters overall voting to remain.

The SNP party political broadcast for the 6 May election made their ambitions clear:

"A Matter of When – Not If"

In a letter to Boris Johnson after the election, Sturgeon immediately brought up the issue of a new referendum, IndyRef2, saying it should be a matter of when – not if – a referendum should be held. The Prime Minister said talk of "ripping our country apart" would be "irresponsible and reckless" and extended an invitation to Sturgeon and Welsh First Minister Mark Drakeford to a Covid recovery summit.

Johnson’s Conservative party includes Unionist in its title, and the party nationally and in Scotland opposes independence. Both the Scottish Labour and Liberal Democrat parties are also pro-union. But the Greens, who secured 8 seats in the new parliament thanks to the regional votes, are pro-independence.

The SNP would like a referendum to take place in the first half of this five-year parliamentary term. They first need to get agreement from Westminster, which is clearly going to be difficult.

Even if a date is set for a referendum, this will be a very different affair from the 2014 ballot. Voters have since experienced the Brexit referendum and the protracted leaving process. In 2014, as for Brexit, voters were faced with a falsely simple choice: should Scotland be independent or not. But many voters at the time worried that the question hid a lot of complex questions that hadn’t been resolved or even discussed: about the pound, borders, joint institutions such as the BBC, NHS, pensions or even vehicle and driver registration. There was much discussion but no definitive answer to whether an independent Scotland could remain part of the EU. Having watched the Brexit unfold, this time voters are likely to demand much more clarity about what it is they are voting for if – or when – they vote.

Copyright(s) :

lennystan/shutterstock

SNP

Tag(s) : "Brexit" "devolution" "elections" "electoral systems" "independence" "Nicola Sturgeon" "referendum" "Scotland" "UK" "UK politics" "Wales"